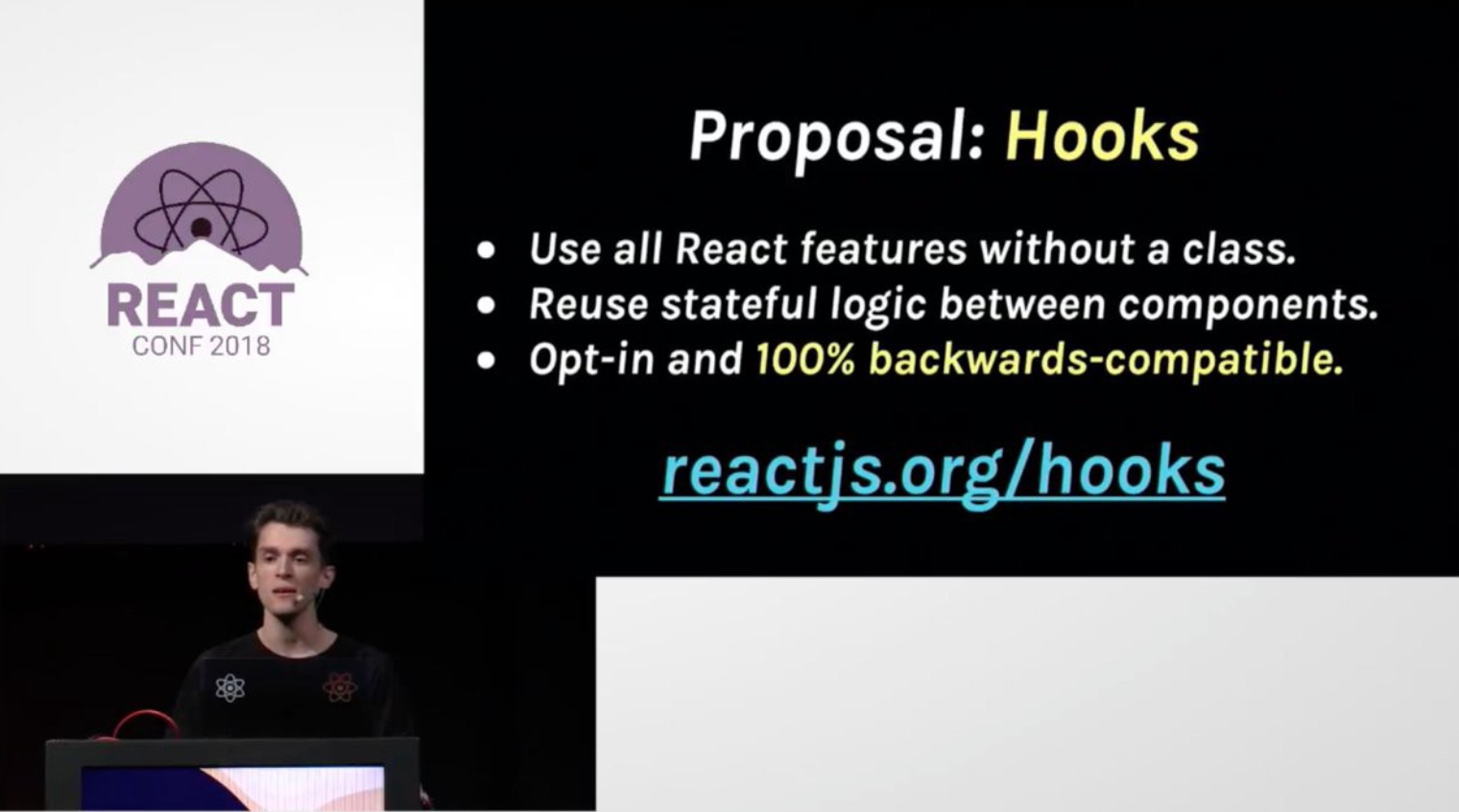

Introducing Hooks

Hooks are a new addition in React 16.8. They let you use state and other React features without writing a class. Ohh yes you don’t need a class to write or have a state in our components so now do we still have stateless functional components or functional components, Yes we have but now we can have state in functional components also

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function Example() {

// Declare a new state variable, which we'll call "count"

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}This new function useState is the first “Hook” we’ll learn about, but this example is just a teaser. Don’t worry if it doesn’t make sense yet!

You can start learning Hooks on the next page. On this page, we’ll continue by explaining why we’re adding Hooks to React and how they can help you write great applications.

Note React 16.8.0 is the first release to support Hooks. When upgrading, don’t forget to update all packages, including React DOM. React Native will support Hooks in the next stable release.

Declaring multiple state variables

You can use the State Hook more than once in a single component:

function ExampleWithManyStates() {

// Declare multiple state variables!

const [age, setAge] = useState(42);

const [fruit, setFruit] = useState('banana');

const [todos, setTodos] = useState([{ text: 'Learn Hooks' }]);

// ...

}The array destructuring syntax lets us give different names to the state variables we declared by calling useState. These names aren’t a part of the useState API. Instead, React assumes that if you call useState many times, you do it in the same order during every render. We’ll come back to why this works and when this is useful later.

But what is a Hook?

Hooks are functions that let you “hook into” React state and lifecycle features from function components. Hooks don’t work inside classes — they let you use React without classes. (We don’t recommend rewriting your existing components overnight but you can start using Hooks in the new ones if you’d like.)

React provides a few built-in Hooks like useState. You can also create your own Hooks to reuse stateful behavior between different components. We’ll look at the built-in Hooks first.

⚡️ Effect Hook

You’ve likely performed data fetching, subscriptions, or manually changing the DOM from React components before. We call these operations “side effects” (or “effects” for short) because they can affect other components and can’t be done during rendering.

The Effect Hook, useEffect, adds the ability to perform side effects from a functional component. It serves the same purpose as componentDidMount, componentDidUpdate, and componentWillUnmount in React classes, but unified into a single API. (We’ll show examples comparing useEffect to these methods in Using the Effect Hook.)

For example, this component sets the document title after React updates the DOM:

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function Example() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

// Similar to componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate:

useEffect(() => {

// Update the document title using the browser API

document.title = `You clicked ${count} times`;

});

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}When you call useEffect, you’re telling React to run your “effect” function after flushing changes to the DOM. Effects are declared inside the component so they have access to its props and state. By default, React runs the effects after every render — including the first render. (We’ll talk more about how this compares to class lifecycles in Using the Effect Hook.)

Effects may also optionally specify how to “clean up” after them by returning a function. For example, this component uses an effect to subscribe to a friend’s online status, and cleans up by unsubscribing from it:

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function FriendStatus(props) {

const [isOnline, setIsOnline] = useState(null);

function handleStatusChange(status) {

setIsOnline(status.isOnline);

}

useEffect(() => {

ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange);

return () => {

ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange);

};

});

if (isOnline === null) {

return 'Loading...';

}

return isOnline ? 'Online' : 'Offline';

}In this example, React would unsubscribe from our ChatAPI when the component unmounts, as well as before re-running the effect due to a subsequent render. (If you want, there’s a way to tell React to skip re-subscribing if the props.friend.id we passed to ChatAPI didn’t change.)

Just like with useState, you can use more than a single effect in a component:

function FriendStatusWithCounter(props) {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

document.title = `You clicked ${count} times`;

});

const [isOnline, setIsOnline] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

ChatAPI.subscribeToFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange);

return () => {

ChatAPI.unsubscribeFromFriendStatus(props.friend.id, handleStatusChange);

};

});

function handleStatusChange(status) {

setIsOnline(status.isOnline);

}

// ...Hooks let you organize side effects in a component by what pieces are related (such as adding and removing a subscription), rather than forcing a split based on lifecycle methods.

without effect Using Classes

In React class components, the render method itself shouldn’t cause side effects. It would be too early — we typically want to perform our effects after React has updated the DOM.

This is why in React classes, we put side effects into componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate. Coming back to our example, here is a React counter class component that updates the document title right after React makes changes to the DOM:

class Example extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

count: 0

};

}

componentDidMount() {

document.title = `You clicked ${this.state.count} times`;

}

componentDidUpdate() {

document.title = `You clicked ${this.state.count} times`;

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {this.state.count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => this.setState({ count: this.state.count + 1 })}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}

}Note how we have to duplicate the code between these two lifecycle methods in class.

This is because in many cases we want to perform the same side effect regardless of whether the component just mounted, or if it has been updated. Conceptually, we want it to happen after every render — but React class components don’t have a method like this. We could extract a separate method but we would still have to call it in two places.

Now let’s see how we can do the same with the useEffect Hook.

Example Using Hooks

We’ve already seen this example at the top of this page, but let’s take a closer look at it:

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function Example() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

document.title = `You clicked ${count} times`;

});

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}What does useEffect do? By using this Hook, you tell React that your component needs to do something after render. React will remember the function you passed (we’ll refer to it as our “effect”), and call it later after performing the DOM updates. In this effect, we set the document title, but we could also perform data fetching or call some other imperative API.

Why is useEffect called inside a component? Placing useEffect inside the component lets us access the count state variable (or any props) right from the effect. We don’t need a special API to read it — it’s already in the function scope. Hooks embrace JavaScript closures and avoid introducing React-specific APIs where JavaScript already provides a solution.

Does useEffect run after every render? Yes! By default, it runs both after the first render and after every update. (We will later talk about how to customize this.) Instead of thinking in terms of “mounting” and “updating”, you might find it easier to think that effects happen “after render”. React guarantees the DOM has been updated by the time it runs the effects.

Rules of Hooks

Hooks are a new addition in React 16.8. They let you use state and other React features without writing a class.

Hooks are JavaScript functions, but you need to follow two rules when using them. We provide a linter plugin to enforce these rules automatically:

Only Call Hooks at the Top Level

Don’t call Hooks inside loops, conditions, or nested functions.

Instead, always use Hooks at the top level of your React function. By following this rule, you ensure that Hooks are called in the same order each time a component renders. That’s what allows React to correctly preserve the state of Hooks between multiple useState and useEffect calls. (If you’re curious, we’ll explain this in depth below.)

Only Call Hooks from React Functions

Don’t call Hooks from regular JavaScript functions. Instead, you can:

-

✅ Call Hooks from React function components.

-

✅ Call Hooks from custom Hooks (we’ll learn about them on the next page).

By following this rule, you ensure that all stateful logic in a component is clearly visible from its source code.

Conclusion :

Keep writing react and add latest features like Hooks to make code look cleaner and more optimized.

Comments