Hack with Javascript Array

The most popular method for creating arrays is using the array literal syntax, which is very straightforward. However, when you want to dynamically create arrays, the array literal syntax may not always be the best method. An alternative method is using the Array constructor.

Here is a simple code snippet showing the use of the Array constructor.

// MORE THAN ONE ARGUMENTS:

// Creates a new array with the arguments as items.

// The length of the array is set to the number of arguments.

var array1 = new Array(1, 2, 3);

console.log(array1); // [1, 2, 3]

console.log(array1.length); // 3

// ONLY ONE(NUMBER) ARGUMENT:

// Creates an array with length set to the number.

// The number must be a positive integer otherwise an error will be thrown.

// Note that the array has no property keys apart from length.

var array2 = new Array(3);

console.log(array2); // Array(3) {length: 3}

console.log(array2.length); // 3

// ONLY ONE(NON-NUMBER) ARGUMENT:

// Creates a new array with the argument as the only item.

// The length of the array is set to 1.

var array3 = new Array("3");

console.log(array3); // ["3"]

console.log(array3.length); // 1From the previous snippet, we can see that the Array constructor creates arrays differently depending on the arguments it receives.

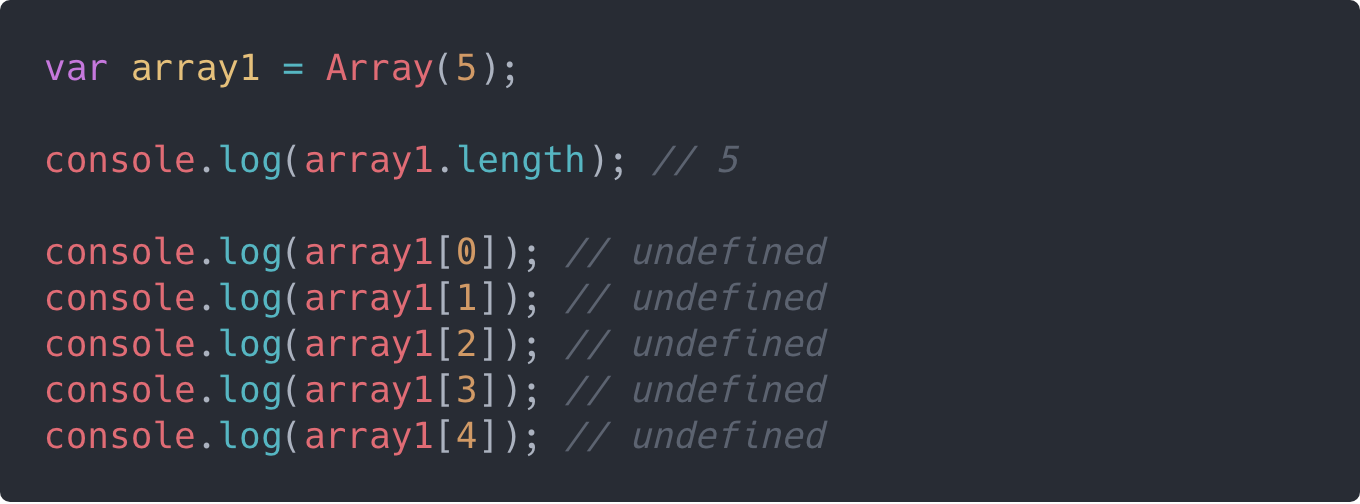

New Arrays: With Defined Length

Let’s look more closely at what happens when creating a new Array of a given length. The constructor just sets the length property of the array to the given length, without setting the keys.

From the above snippet, you may be tempted to think that each key in the array was set to a value of undefined. But the reality is that those keys were never set (they don’t exist).

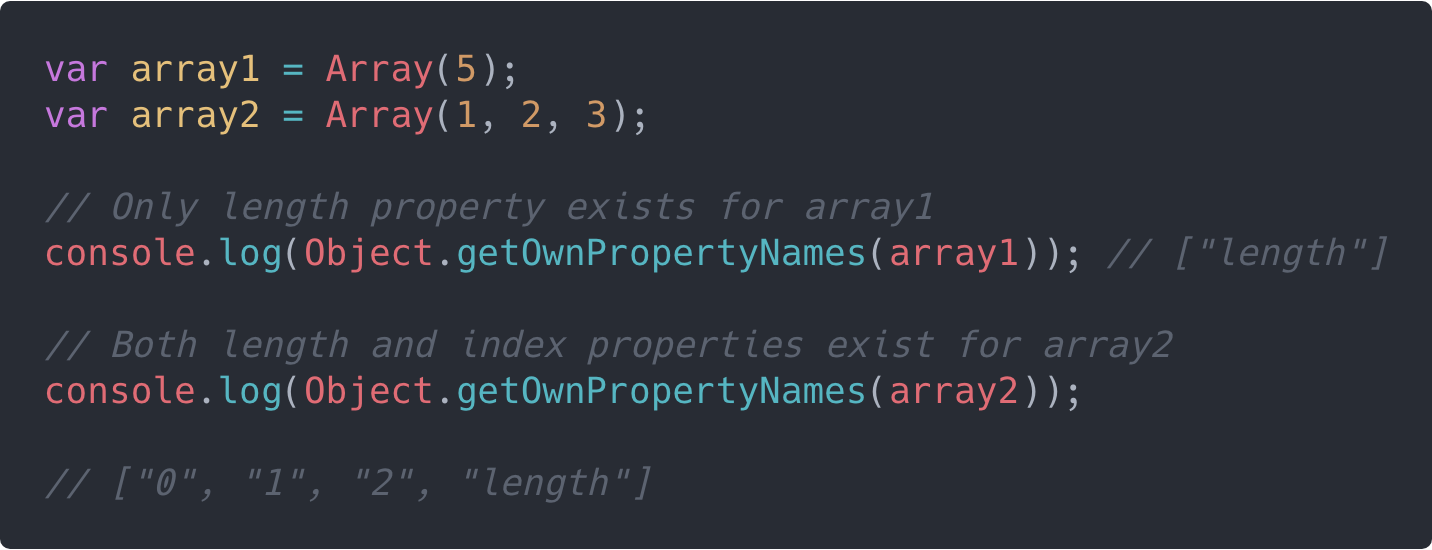

The following illustration makes it clearer:

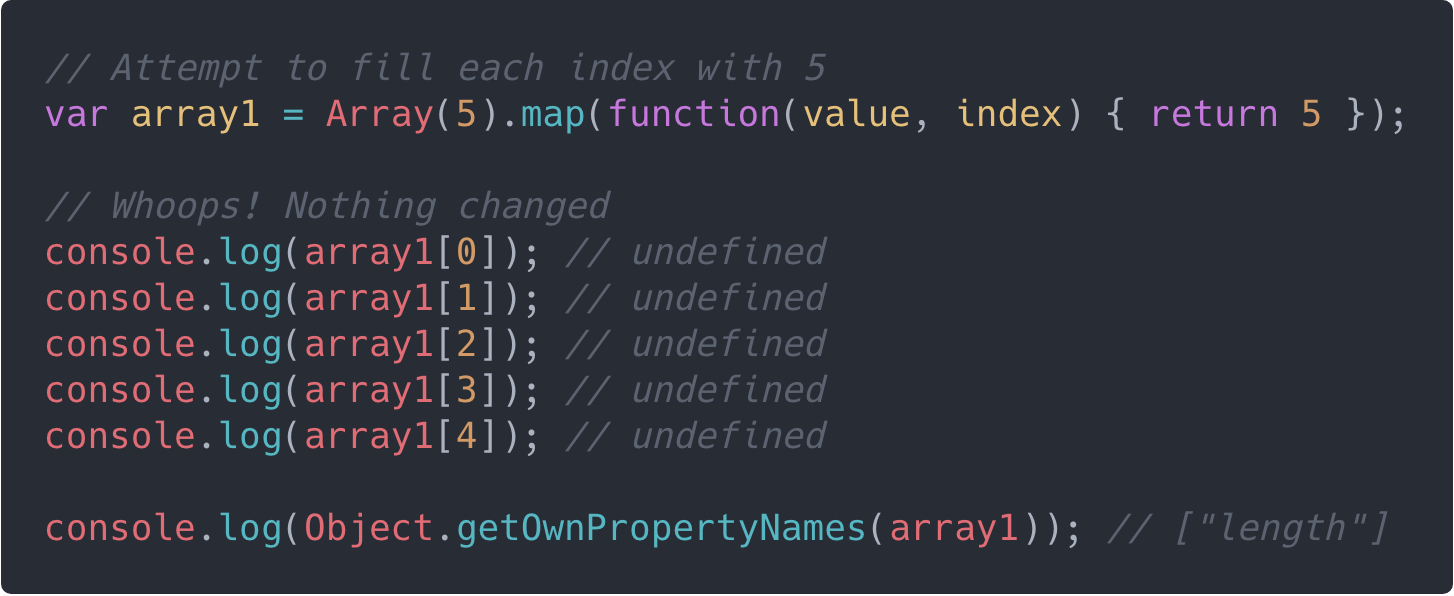

This makes it useless to attempt to use any of the array iteration methods such as map(), filter() or reduce() to manipulate the array. Let’s say we want to fill each index in the array with the number 5 as a value. We will attempt the following:

We can see that map() didn’t work here, because the index properties don’t exist on the array — only the length property exists.

Let’s see different ways we can fix this issue.

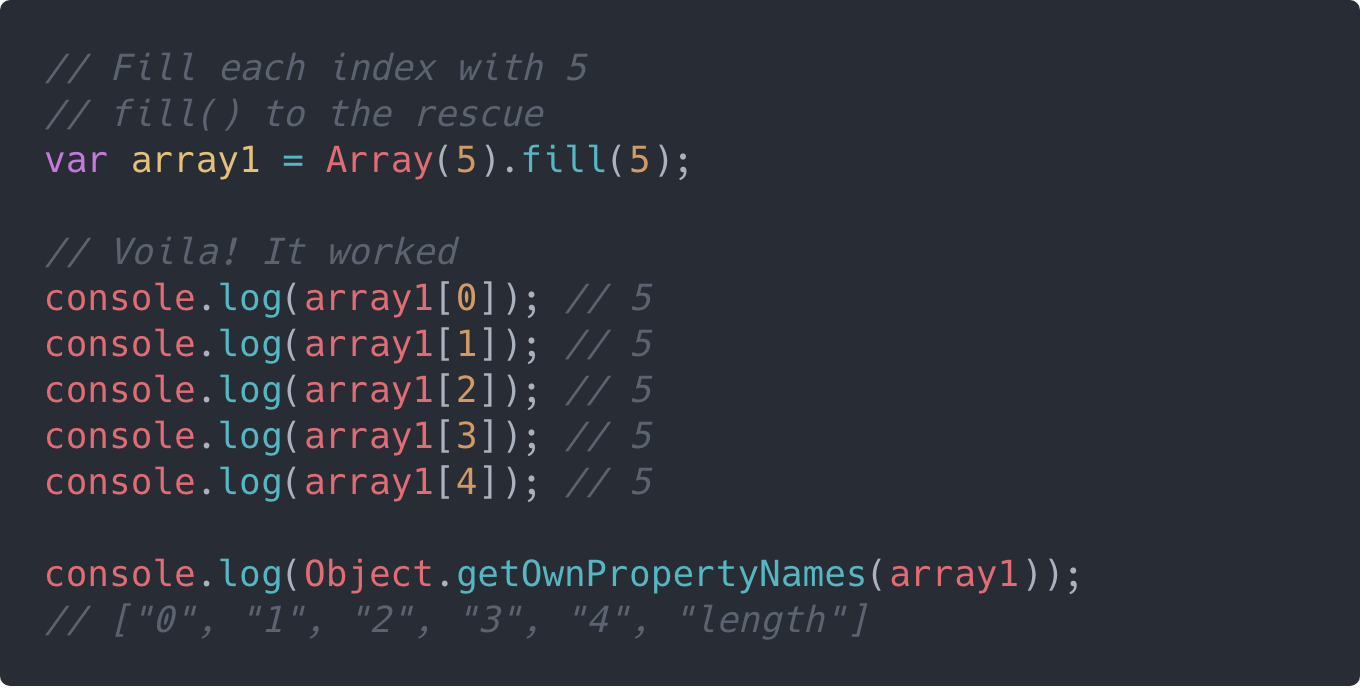

1. Using Array.prototype.fill()

The fill() method fills all the elements of an array from a start index to an end index with a static value. The end index is not included. You can learn more about fill() here.

Note that fill() will only work in browsers with ES6 support.

Here is a simple illustration:

Here, we have been able to fill all the elements of our created array with 5. You can set any static value for different indexes of the array using the fill()method.

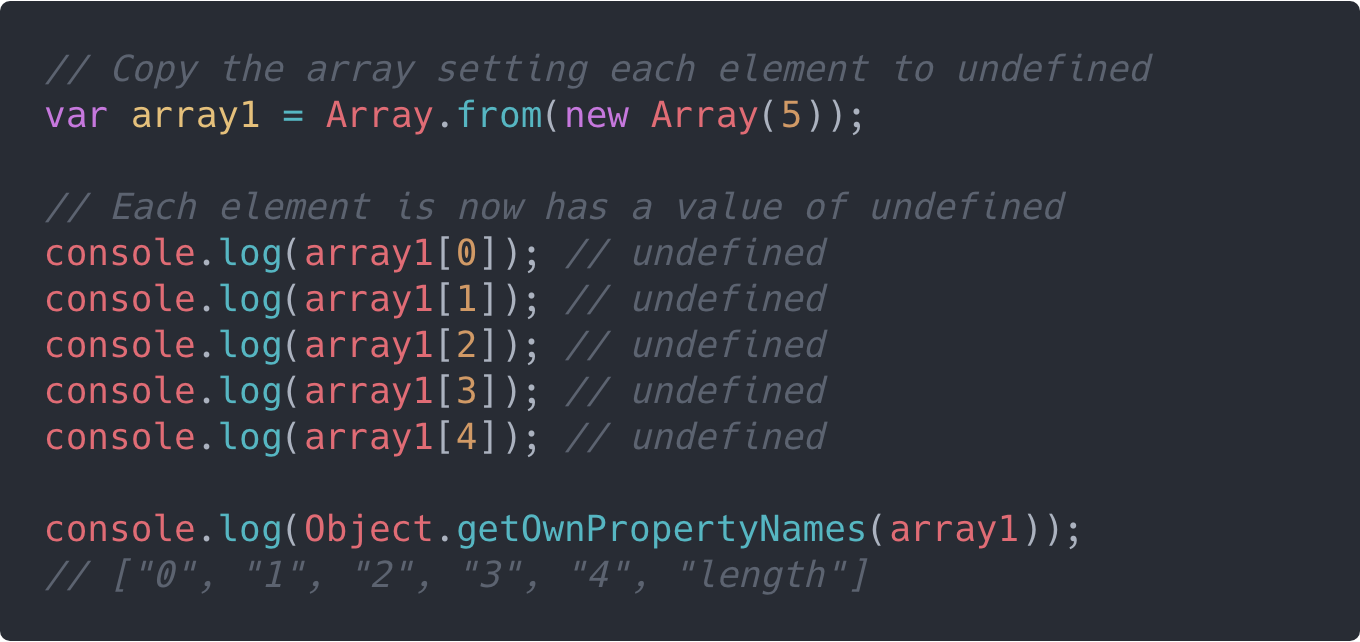

2. Using Array.from()

The Array.from() method creates a new, shallow-copied Array instance from an array-like or iterable object. You can learn more about Array.from()here.

Note that Array.from() will only work in browsers with ES6 support.

Here is a simple illustration:

Here, we now have true undefined values set for each element of the array using Array.from(). This means we can now go ahead and use methods like .map() and .filter() on the array, since the index properties now exist.

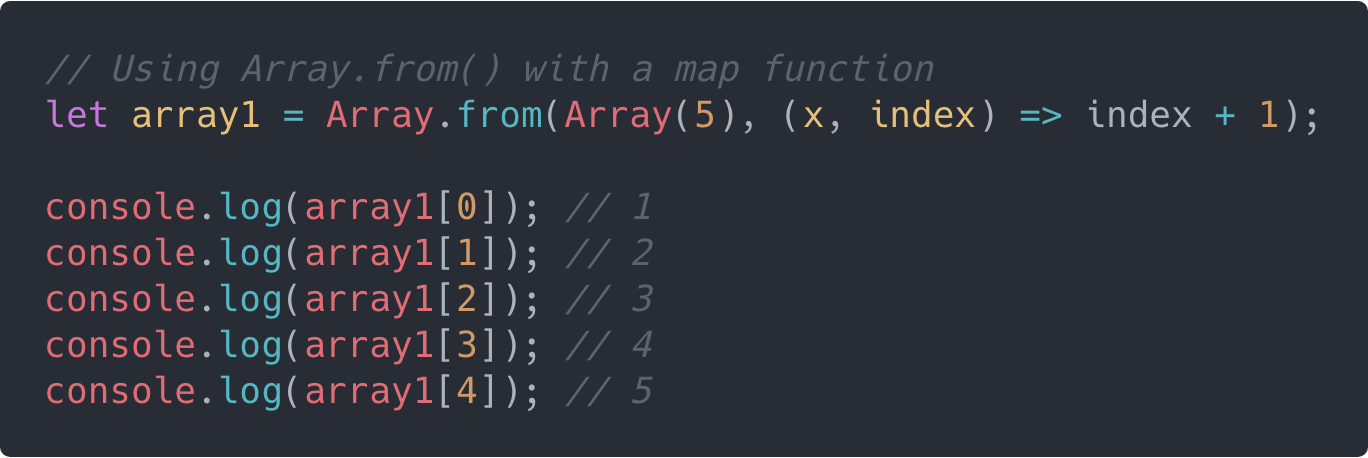

One more thing worth noting about Array.from() is that it can take a second argument, which is a map function. It will be called on every element of the array. This makes it redundant calling .map() after Array.from().

Here is a simple example:

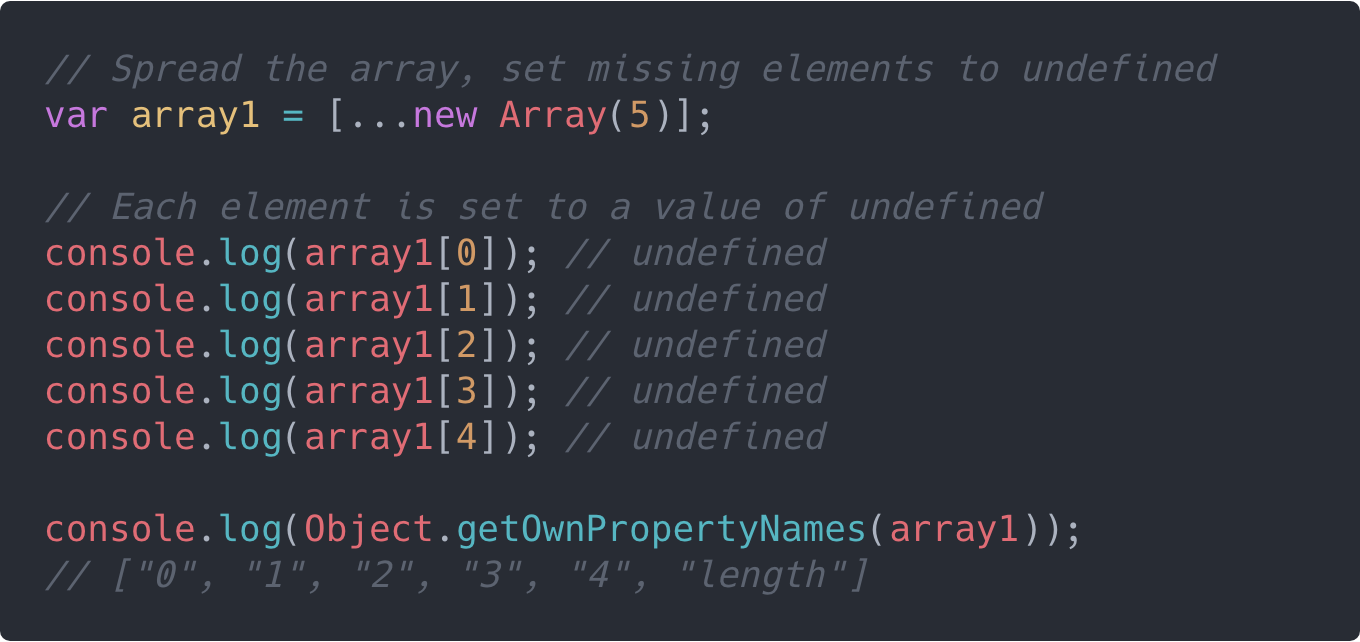

3. Using the Spread Operator

The spread operator* *(...), added in ES6, can be used to spread the elements of the array, setting the missing elements to a value of undefined. This will produce the same result as simply calling Array.from() with just the array as the only argument.

Here is a simple illustration of using the spread operator:

You can go ahead and use methods like .map() and .filter() on the array, since the index properties now exist.

Using Array.of()

Just like we saw with creating new arrays using the Array constructor or function, Array.of() behaves in a very similar fashion. In fact, the only difference between Array.of() and Array is in how they handle a single integer argument passed to them.

While Array.of(5) creates a new array with a single element, 5, and a length property of 1, Array(5) creates a new empty array with 5 empty slots and a length property of 5.

var array1 = Array.of(5); // [5]

var array2 = Array(5); // Array(5) {length: 5}Besides this major difference, Array.of() behaves just like the Arrayconstructor. You can learn more about Array.of() here.

Note that Array.of() will only work in browsers with ES6 support.

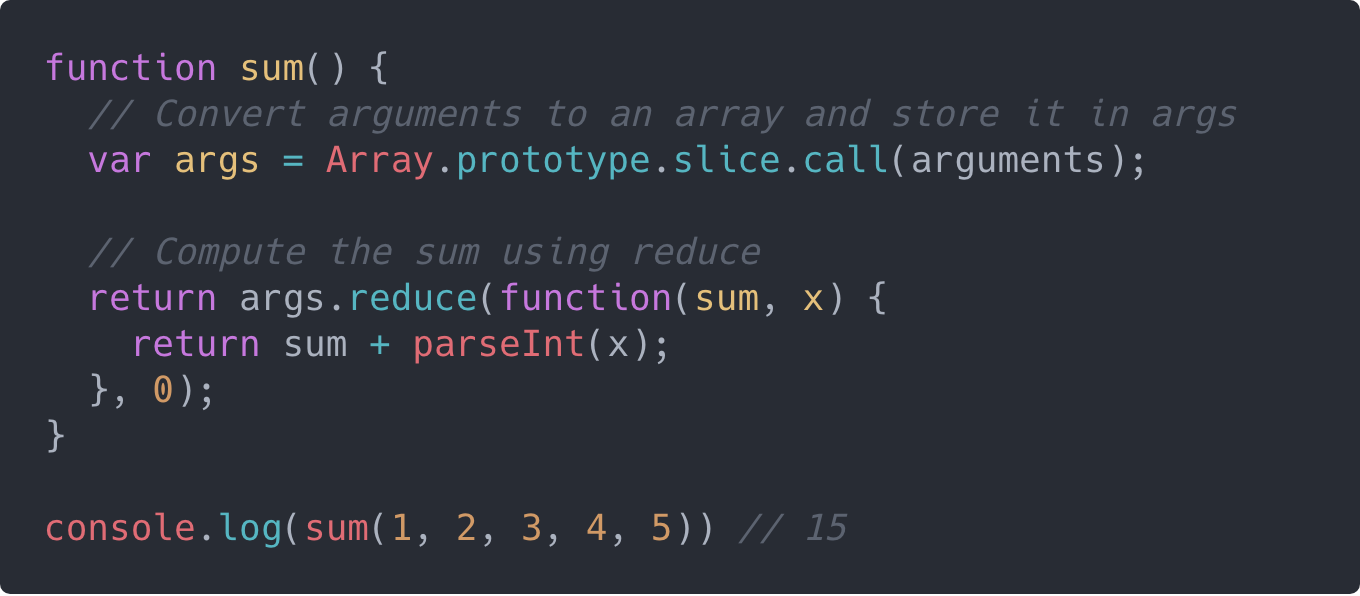

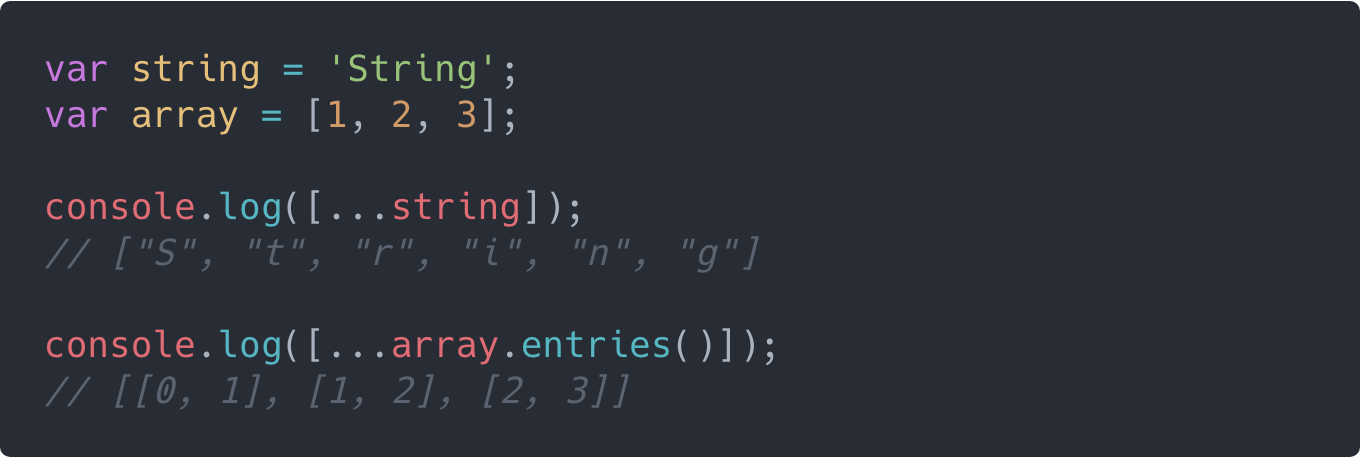

Converting to Arrays: Array-likes and Iterables

If you have been writing JavaScript functions long enough, you should already know about the arguments object — which is an array-like object available in every function to hold the list of arguments the function received. Although the arguments object looks much like an array, it does not have access to the Array.prototype methods.

Prior to ES6, you would usually see a code snippet like the following when trying to convert the arguments object to an array:

With Array.from() or the spread operator, you can conveniently convert any array-like object into an array. Hence, instead of doing this:

var args = Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments);you can do either of these:

// Using Array.from()

var args = Array.from(arguments);

// Using the Spread operator

var args = [...arguments];These also apply to iterables as shown in the following illustration:

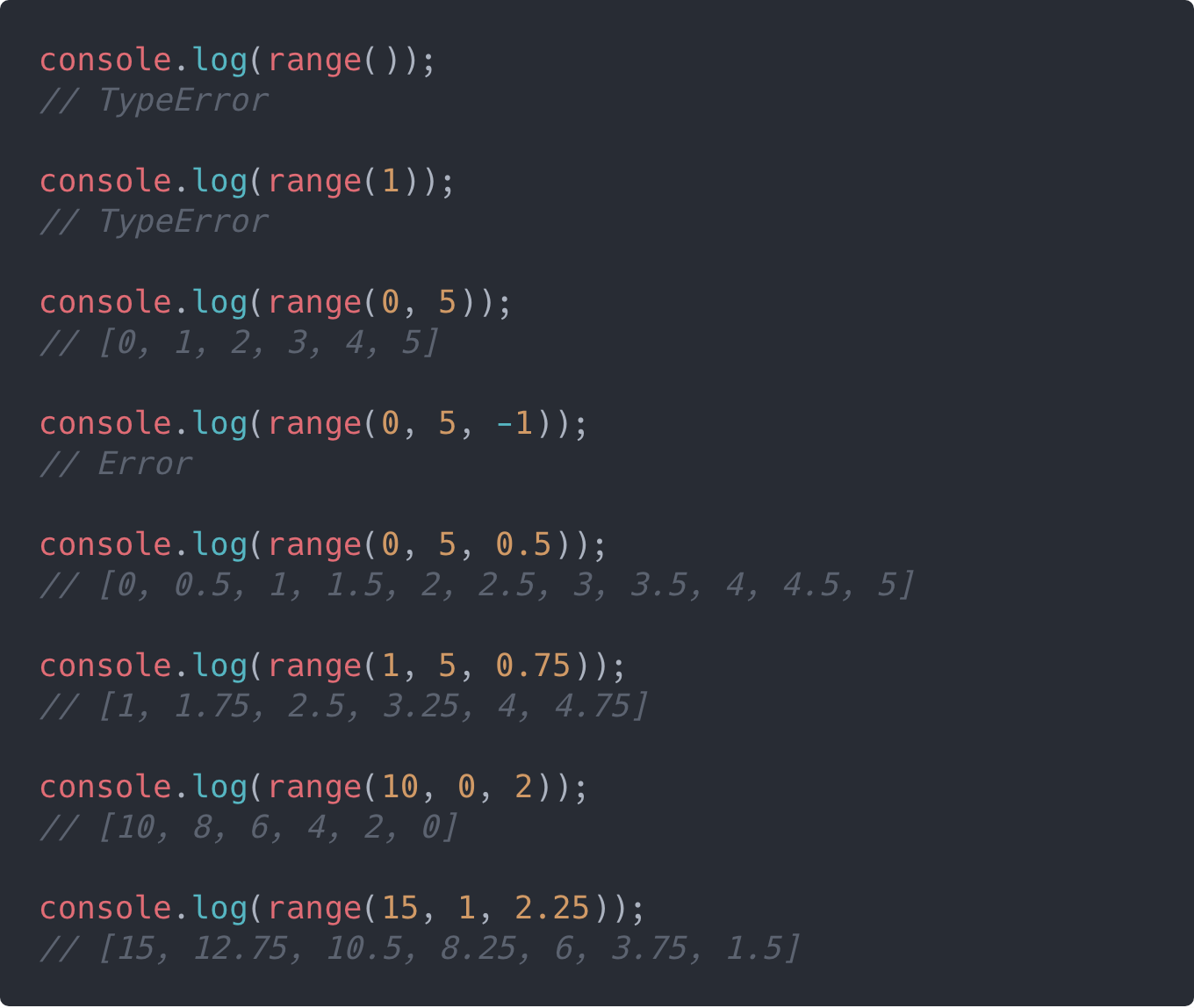

Case Study: Range Function

As a case study before we proceed, we will create a simple range() function to implement the new array hack we just learned. The function has the following signature:

range(start: number, end: number, step: number) => Array<number>Here is the code snippet:

/**

* range()

*

* Returns an array of numbers between a start number and an end number incremented

* sequentially by a fixed number(step), beginning with either the start number or

* the end number depending on which is greater.

*

* @param {number} start (Required: The start number.)

* @param {number} end (Required: The end number. If end is less than start,

* then the range begins with end instead of start and decrements instead of increment.)

* @param {number} step (Optional: The fixed increment or decrement step. Defaults to 1.)

*

* @return {array} (An array containing the range numbers.)

*

* @throws {TypeError} (If any of start, end and step is not a finite number.)

* @throws {Error} (If step is not a positive number.)

*/

function range(start, end, step = 1) {

// Test that the first 3 arguments are finite numbers.

// Using Array.prototype.every() and Number.isFinite().

const allNumbers = [start, end, step].every(Number.isFinite);

// Throw an error if any of the first 3 arguments is not a finite number.

if (!allNumbers) {

throw new TypeError('range() expects only finite numbers as arguments.');

}

// Ensure the step is always a positive number.

if (step <= 0) {

throw new Error('step must be a number greater than 0.');

}

// When the start number is greater than the end number,

// modify the step for decrementing instead of incrementing.

if (start > end) {

step = -step;

}

// Determine the length of the array to be returned.

// The length is incremented by 1 after Math.floor().

// This ensures that the end number is listed if it falls within the range.

const length = Math.floor(Math.abs((end - start) / step)) + 1;

// Fill up a new array with the range numbers

// using Array.from() with a mapping function.

// Finally, return the new array.

return Array.from(Array(length), (x, index) => start + index * step);

}In this code snippet, we used Array.from() to create the new range array of dynamic length and then populate it sequentially incremented numbers by providing a mapping function.

Note that the above code snippet will not work for browsers without ES6 support except if you use polyfills.

Here are some results from calling the range() function defined in the above code snippet:

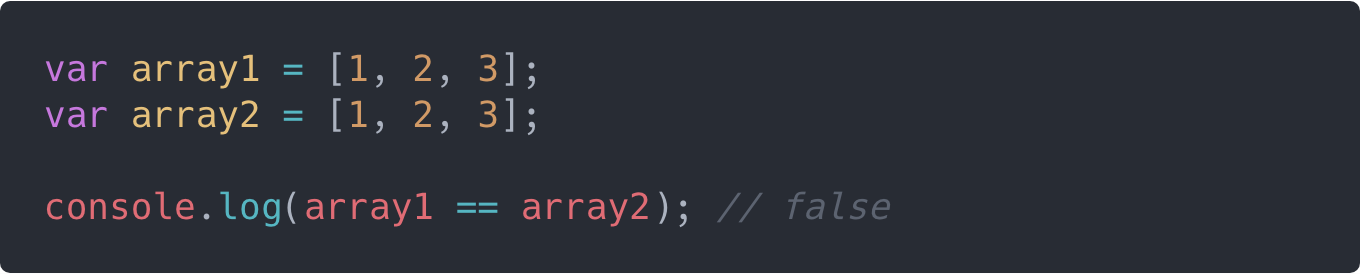

In JavaScript, arrays and objects are reference types. This means that when a variable is assigned an array or object, what gets assigned to the variable is a reference to the location in memory where the array or object was stored.

Arrays, just like every other object in JavaScript, are reference types. This means that arrays are copied by reference and not by value.

Storing reference types this way has the following consequences:

1. Similar arrays are not equal.

Here, we see that although array1 and array2 contain seemingly the same array specifications, they are not equal. This is because the reference to each of the arrays points to a different location in memory.

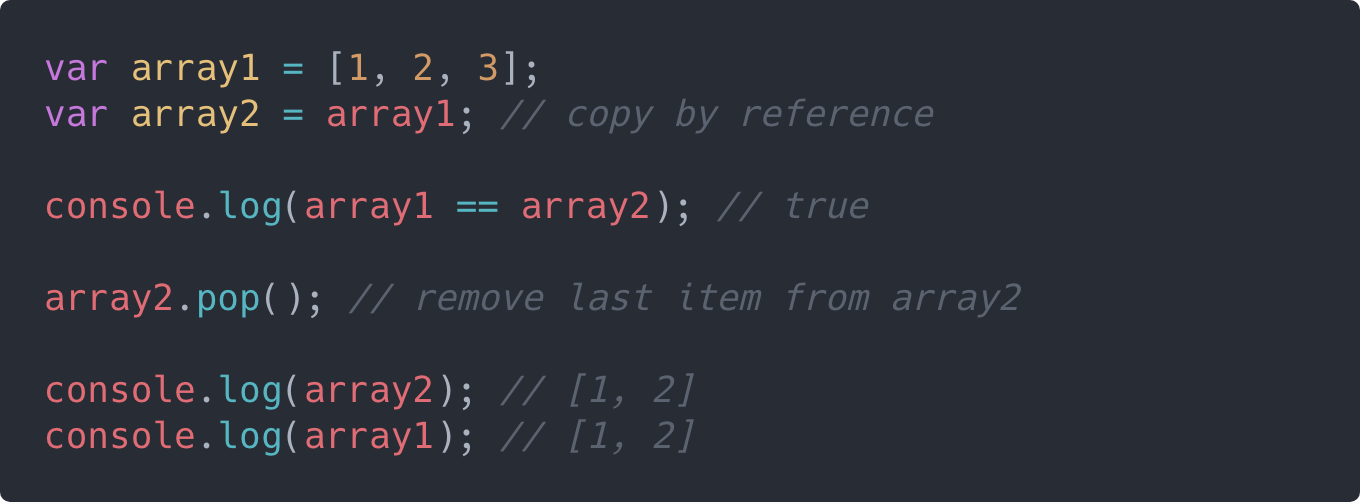

2. Arrays are copied by reference and not by value.

Here, we attempt to copy array1 to array2, but what we are basically doing is pointing array2 to the same location in memory that array1 points to. Hence, both array1 and array2 point to the same location in memory and are equal.

The implication of this is that when we make a change to array2 by removing the last item, the last item of array1 also gets removed. This is because the change was actually made to the array stored in memory, whereas array1and array2 are just pointers to that same location in memory where the array is stored.

Cloning Arrays: The Hacks

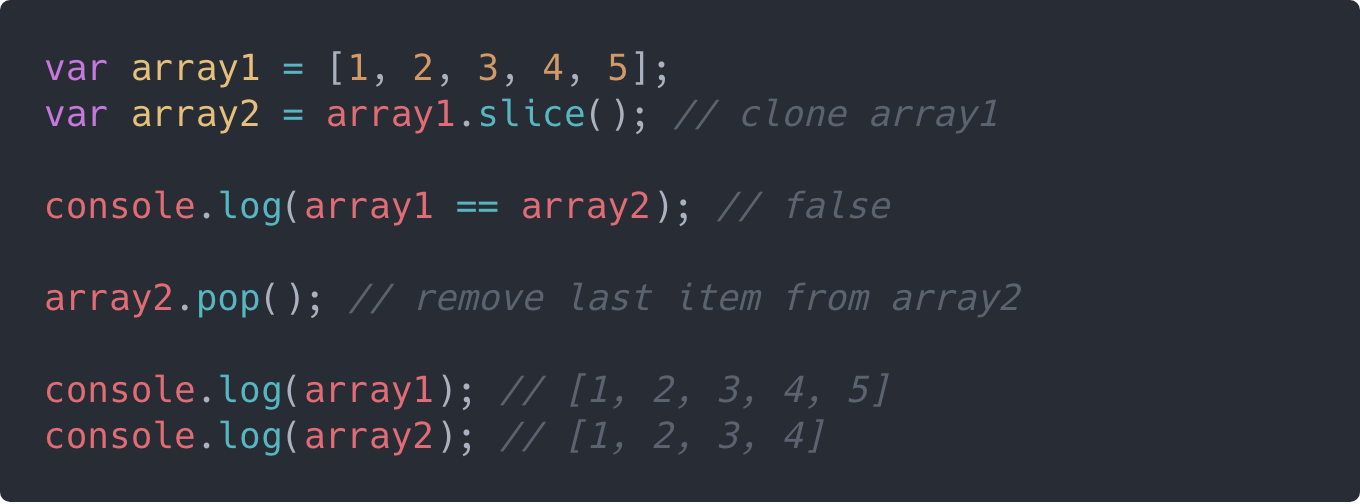

1. Using Array.prototype.slice()

The slice() method creates a shallow copy of a portion of an array without modifying the array. You can learn more about slice() here.

The trick is to call slice() either with0 as the only argument or without any arguments at all:

// with O as only argument

array.slice(0);

// without argument

array.slice();Here is a simple illustration of cloning an array with slice():

Here, you can see that array2 is a clone of array1 with the same items and length. However, they point to different locations in memory, and as a result are not equal. You also notice that when we make a change to array2 by removing the last item, array1 remains unchanged.

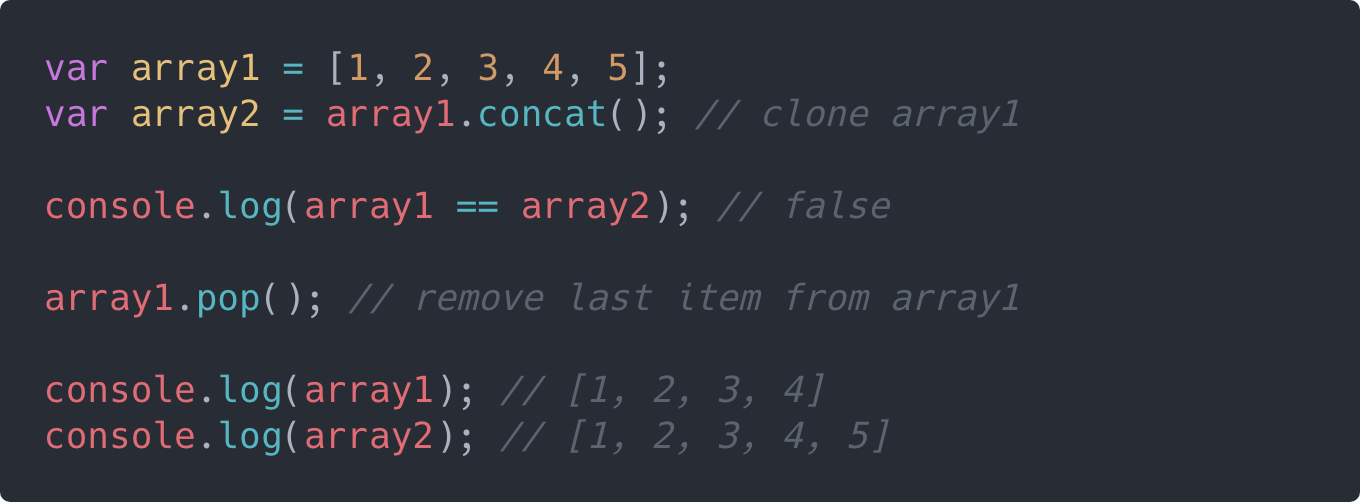

2. Using Array.prototype.concat()

The concat() method is used to merge two or more arrays, resulting in a new array, while the original arrays are left unchanged. You can learn more about concat() here.

The trick is to call concat() either with an empty array([]) as argument or without any arguments at all:

// with an empty array

array.concat([]);

// without argument

array.concat();Cloning an array with concat() is quite similar to using slice(). Here is a simple illustration of cloning an array with concat():

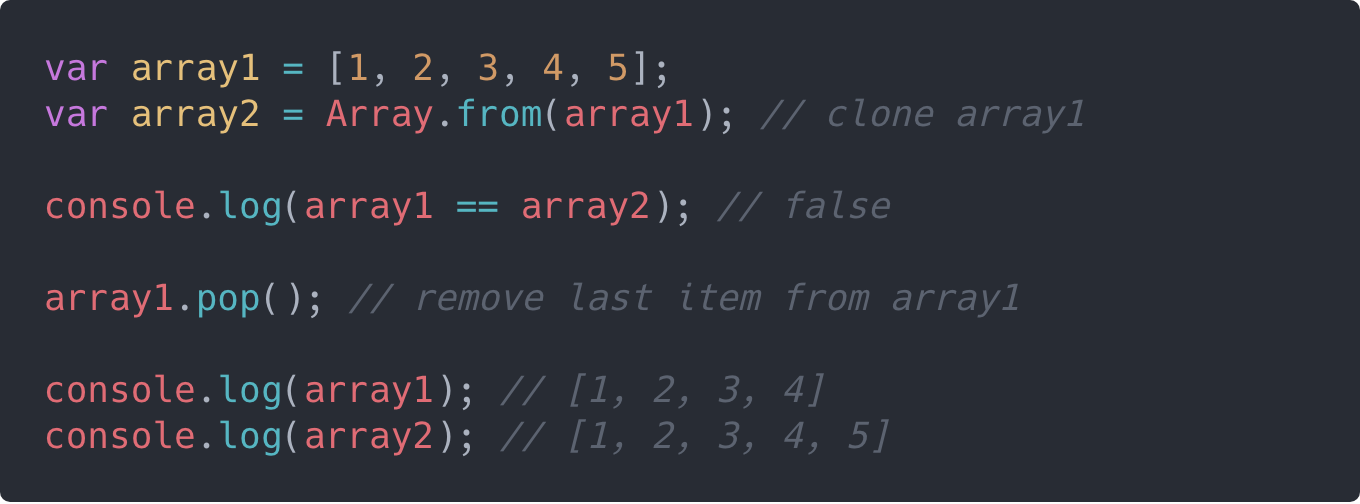

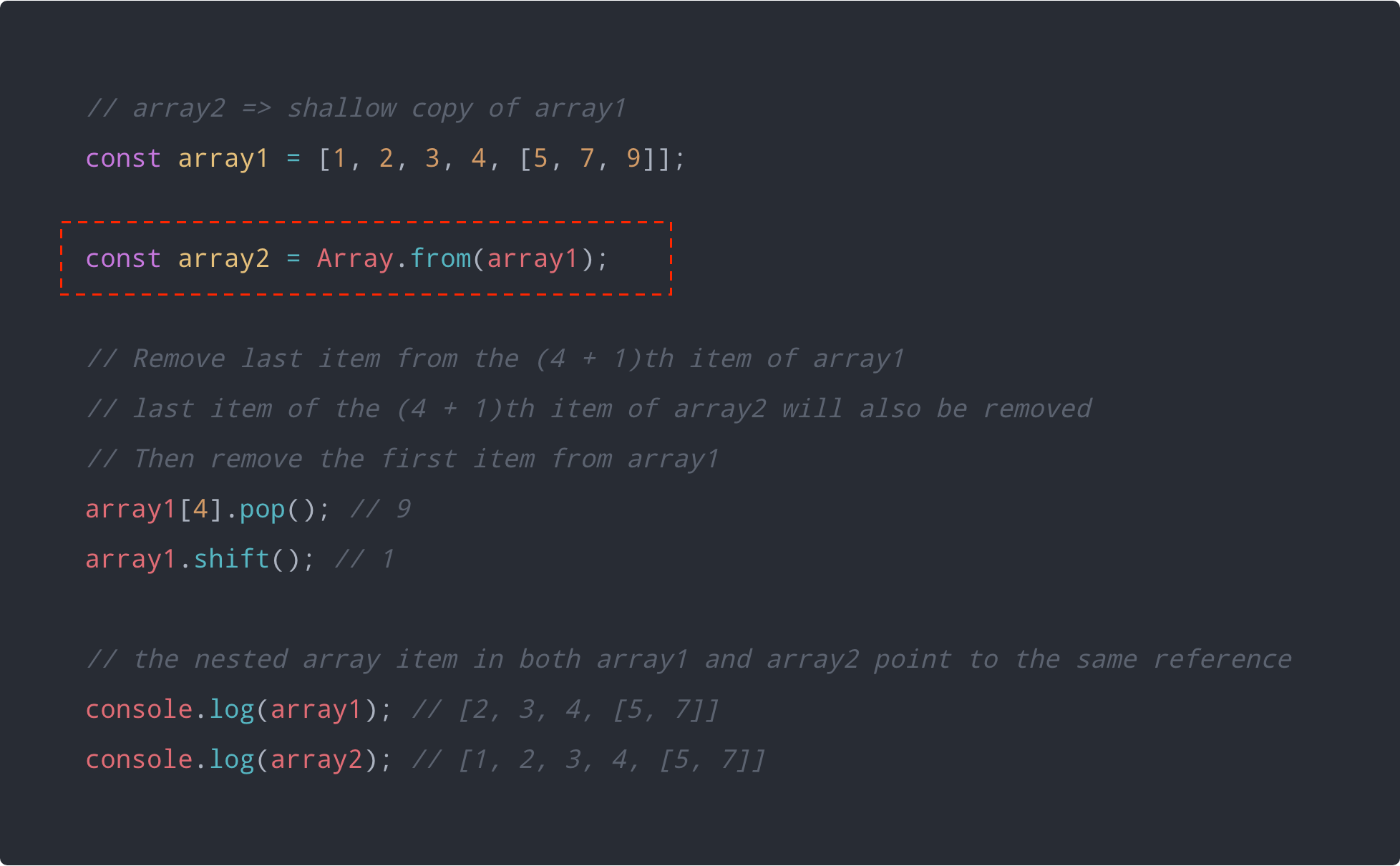

3. Using Array.from()

Like we saw earlier, Array.from() can be used to create a new array which is a shallow-copy of the original array. Here is a simple illustration:

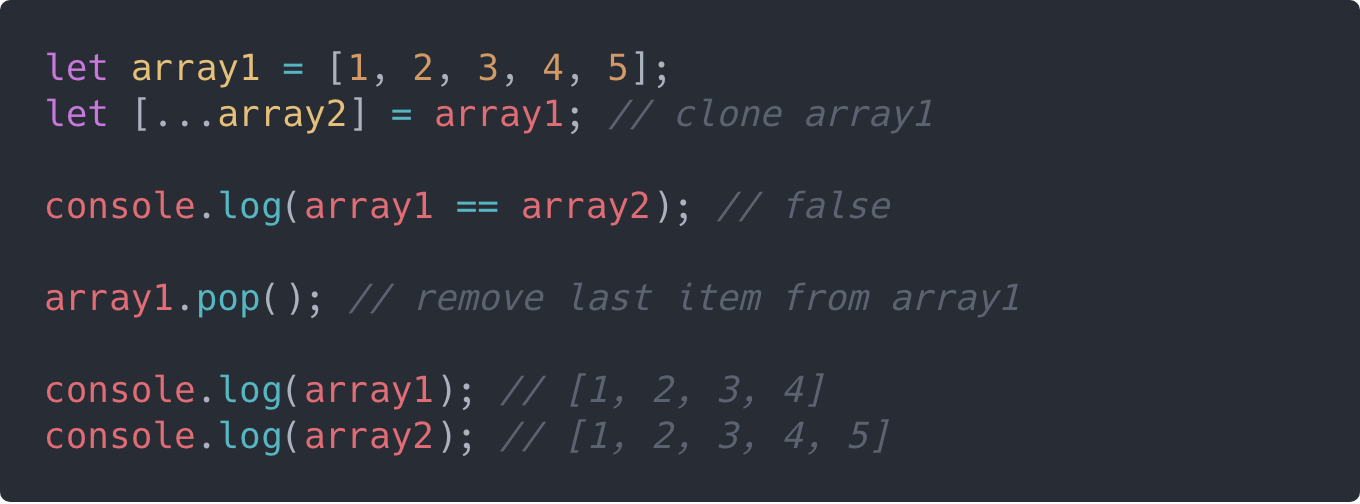

4. Using Array Destructuring

With ES6, we have some more powerful tools in our toolbox such as destructuring, spread* *operator, arrow functions, and so on. Destructuring is a very powerful tool for extracting data from complex types like arrays and objects.

The trick is to use a technique called rest parameters, which involves a combination of array destructuring and the spread operator as shown in the following snippet:

let [...arrayClone] = originalArray;The above snippet creates a variable named arrayClone which is a clone of the originalArray. Here is a simple illustration of cloning an array using array destructuring:

Cloning: Shallow versus Deep

All the array cloning techniques we’ve explored so far produce a shallow copyof the array. This won’t be an issue if the array contains only primitive values. However, if the array contains nested object references, those references will remain intact even when the array is cloned.

Here is a very simple demonstration of this:

Notice that modifying the nested array in array1 also modified the nested array in array2 and vice-versa.

The solution to this problem is to create a deep copy of the array and there are a couple of ways to do this.

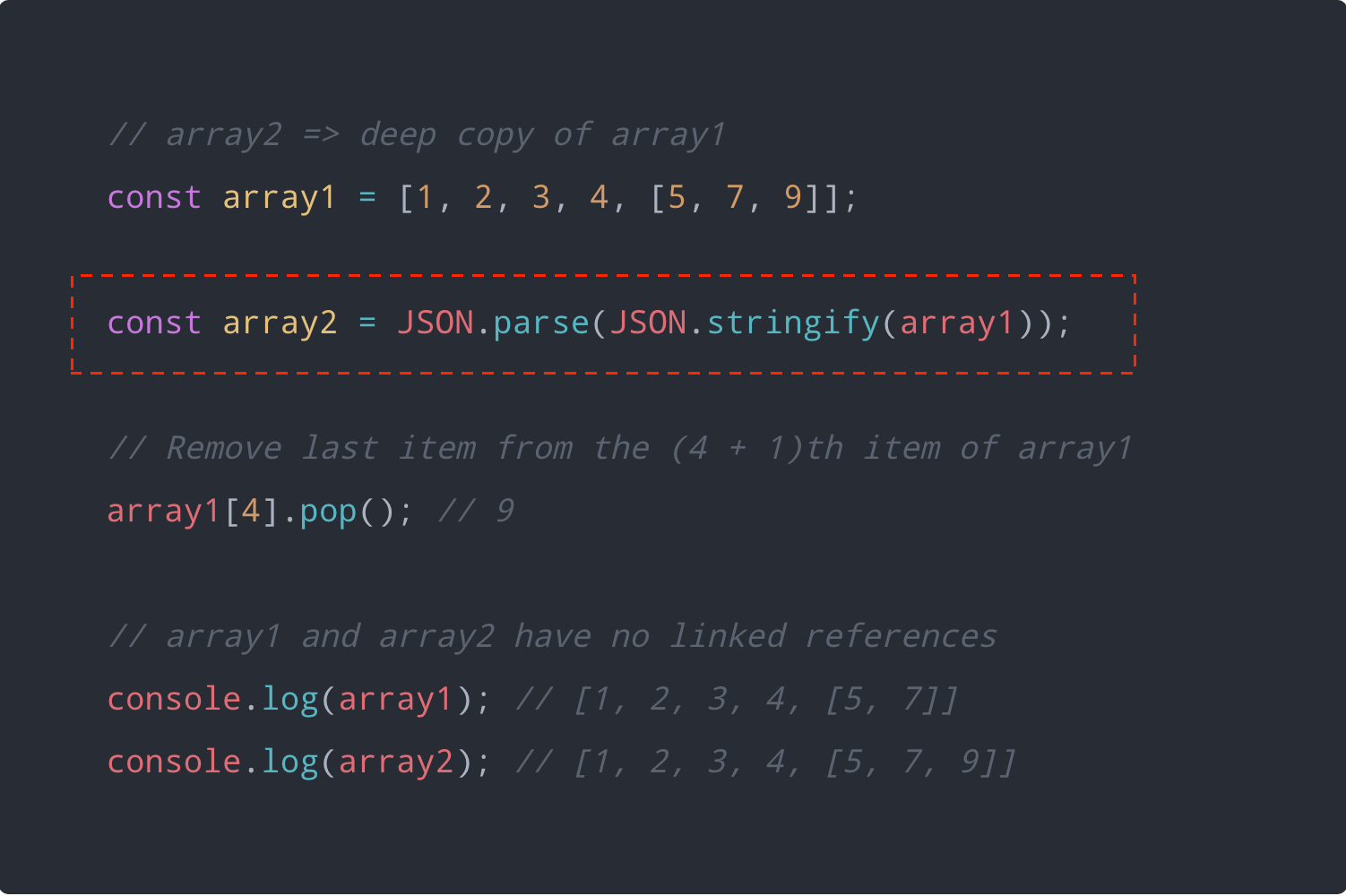

1. The JSON technique

The easiest way to create a deep copy of an array is by using a combination of JSON.stringify() and JSON.parse().

JSON.stringify() converts a JavaScript value to a valid JSON string, while JSON.parse() converts a JSON string to a corresponding JavaScript value or object.

Here is a simple example:

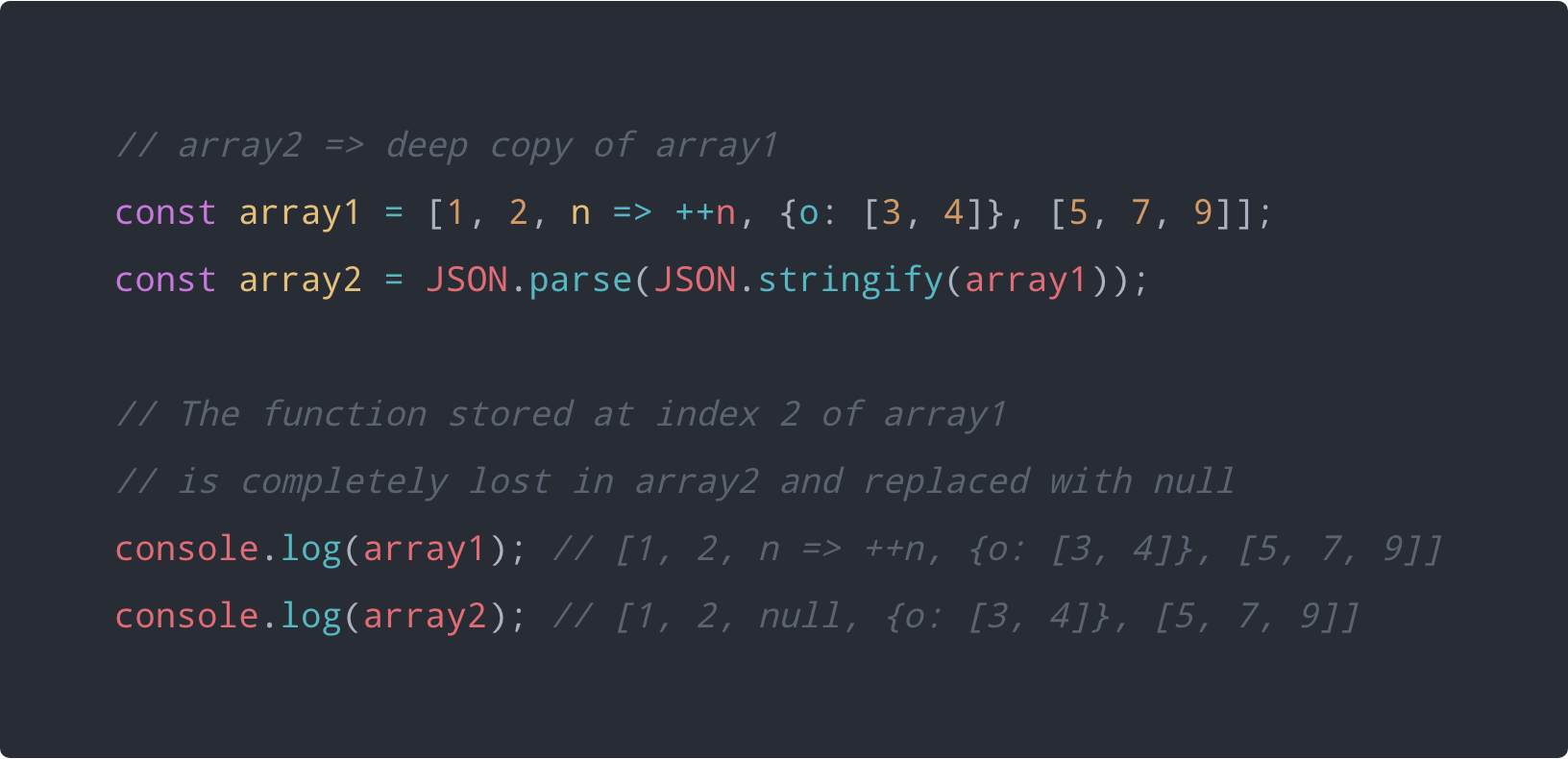

The JSON technique has some flaws especially when values other than strings, numbers and booleans are involved.

These flaws in the JSON technique can be majorly attributed to the manner in which the JSON.stringify() method converts values to JSON string.

Here is a simple demonstration of this flaw in trying to JSON.stringify() a value containing nested function.

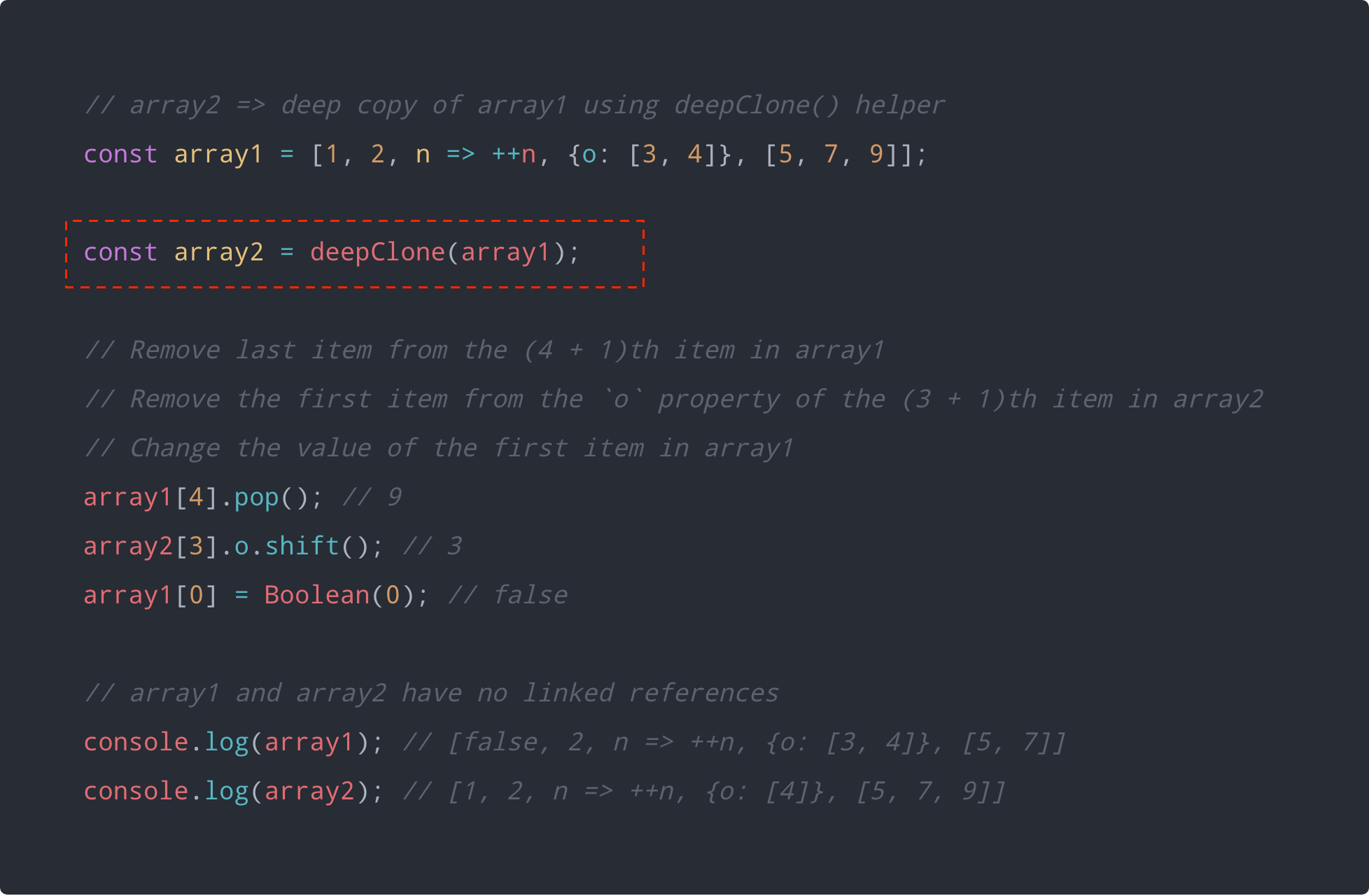

2. Deep Copy Helper

A viable alternative to the JSON technique will be to implement your own deep copy helper function for cloning reference types whether they be arrays or objects.

Here is a very simple and minimalistic deep copy function called deepClone:

function deepClone(o) {

// Construct the copy `output` array or object.

// Use `Array.isArray()` to check if `o` is an array.

// If `o` is an array, set the copy `output` to an empty array (`[]`).

// Otherwise, set the copy `output` to an empty object (`{}`).

//

// If `Array.isArray()` is not supported, this can be used as an alternative:

// Object.prototype.toString.call(o) === '[object Array]'

// However, it is a fragile alternative.

const output = Array.isArray(o) ? [] : {};

// Loop through all the properties of `o`

for (let i in o) {

// Get the value of the current property of `o`

const value = o[i];

// If the value of the current property is an object and is not null,

// deep clone the value and assign it to the same property on the copy `output`.

// Otherwise, assign the raw value to the property on the copy `output`.

output[i] = value !== null && typeof value === 'object' ? deepClone(value) : value;

}

// Return the copy `output`.

return output;

}Now this is not the best of deep copy functions out there, like you will soon see with some JavaScript libraries — however, it performs deep copying to a pretty good extent.

3. Using JavaScript Libraries

The deep copy helper function we just defined is not robust enough in cloning all the kinds of JavaScript data that may be nested within complex objects or arrays.

JavaScript libraries like Lodash and jQuery provide more robust deep copy utility functions with support for different kinds of JavaScript data.

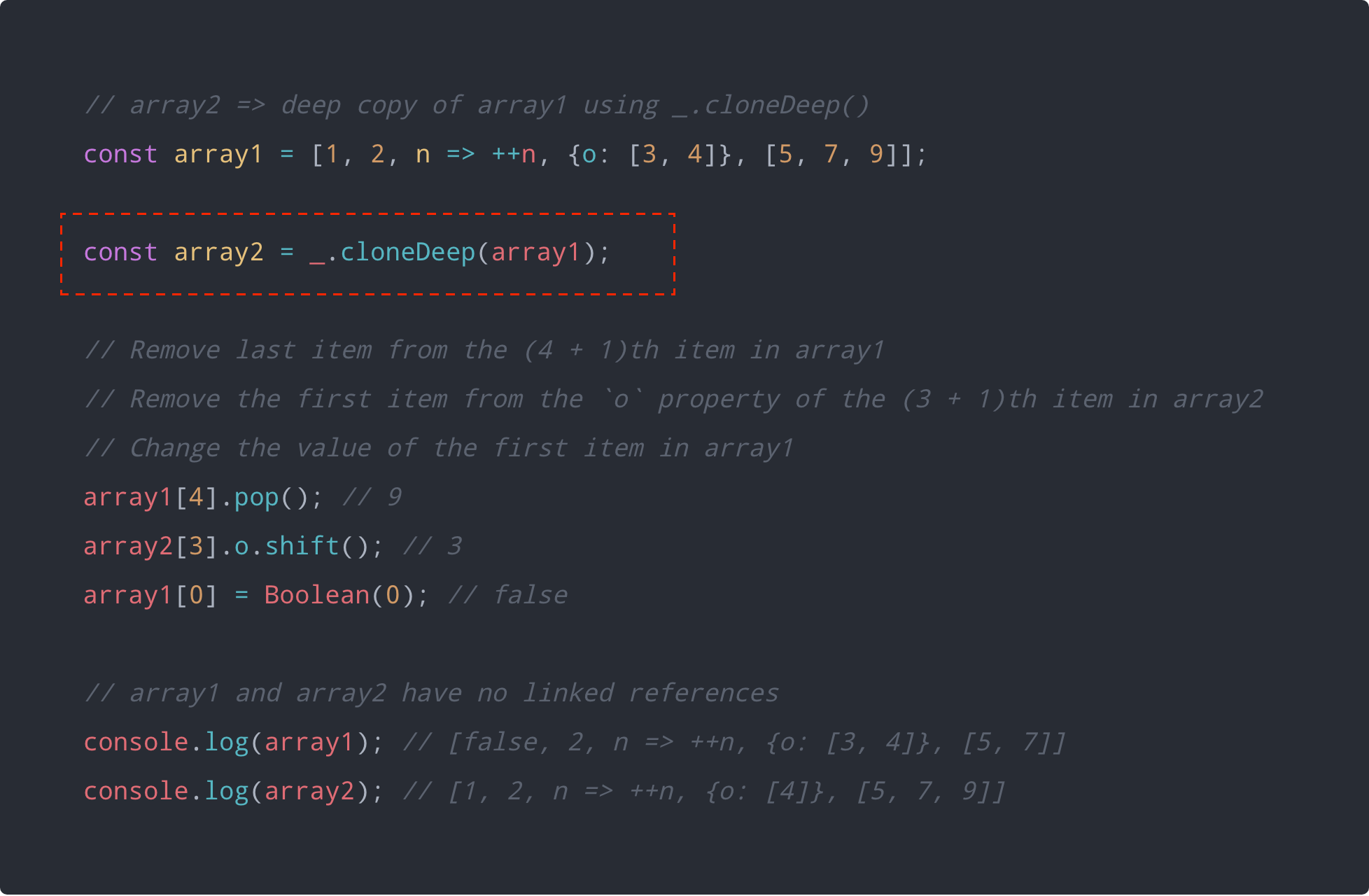

Here is an example that uses _.cloneDeep() from the Lodash library:

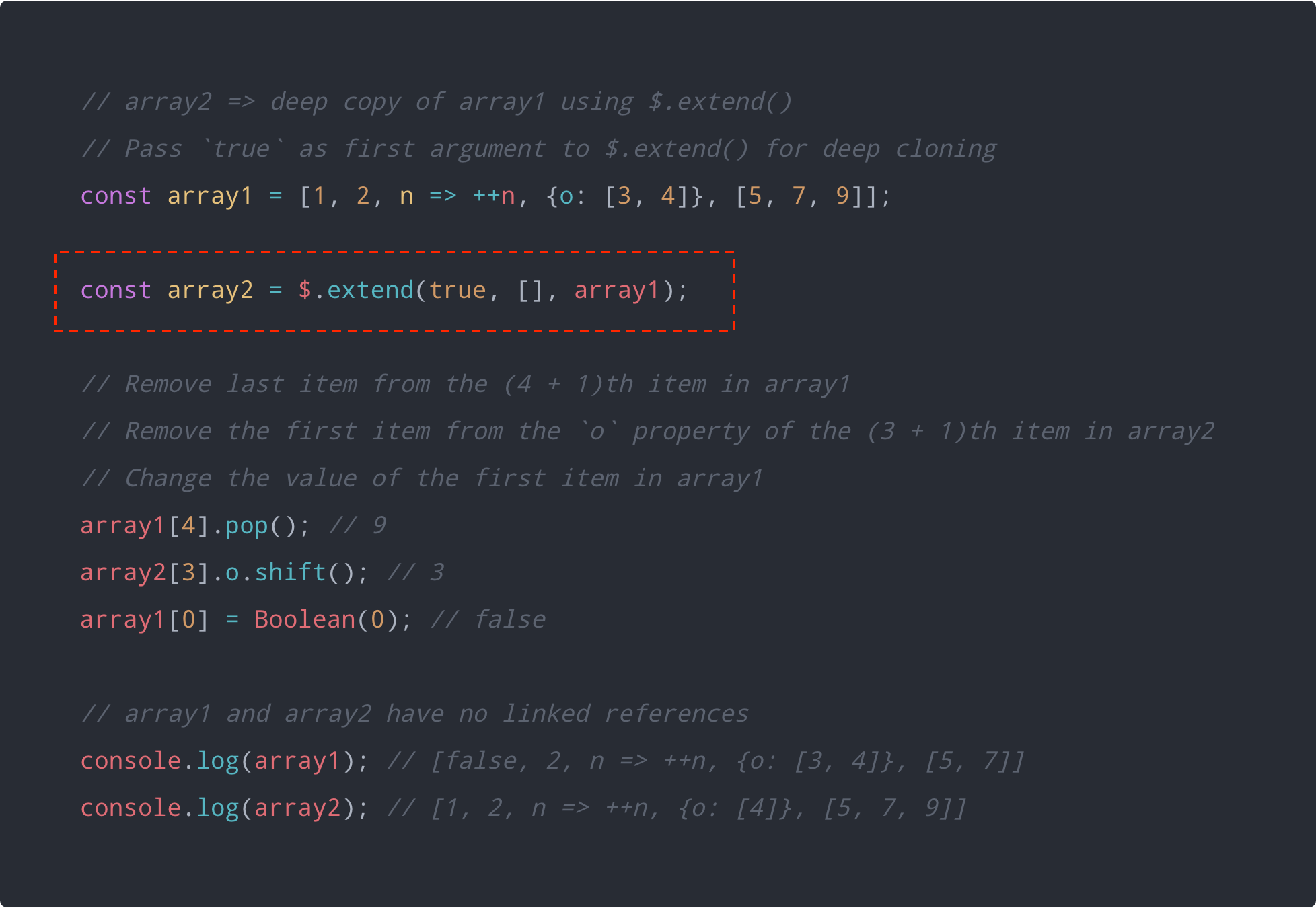

Here is the same example but using $.extend() from the jQuery library:

Conclusion

In this article, we have been able to explore several tips and tricks about javascript using ES6 and ES7, we have mode videos on youtube talking about same or code available on scrimba too

Comments