State-Driven UI frameworks (React, Angular and Vue) are popular for a reason. They offload a big headache — tying state to the view — to the framework.

A commonly discussed “improvement” to the out of the box usage on these is using a *store. *The originator being Redux, of React.

These are all children of the founding idea called *Flux. *Flux is a pattern, not an implementation.

I had a chance to look into Angular’s take on this: called ngrx/store.

Here’s my thoughts about how it works and whether your project needs it.

Hint: probably not.

Flux and the Idea of a Store

The essence of modern UI frameworks like Angular is to create the interface as a manifestation of the application state. Let’s begin by looking at what this means, and then see how using a store fits in. The use of ngrx/store is simply a more rigorous extension of the essence.

Every application has state. In Angular, we bind that state to the UI so that the interaction of the interface and the state is managed automatically. This eliminates the work and complexity of the developer having to manage this interaction. The actual management of the state itself becomes both more important and more capable.

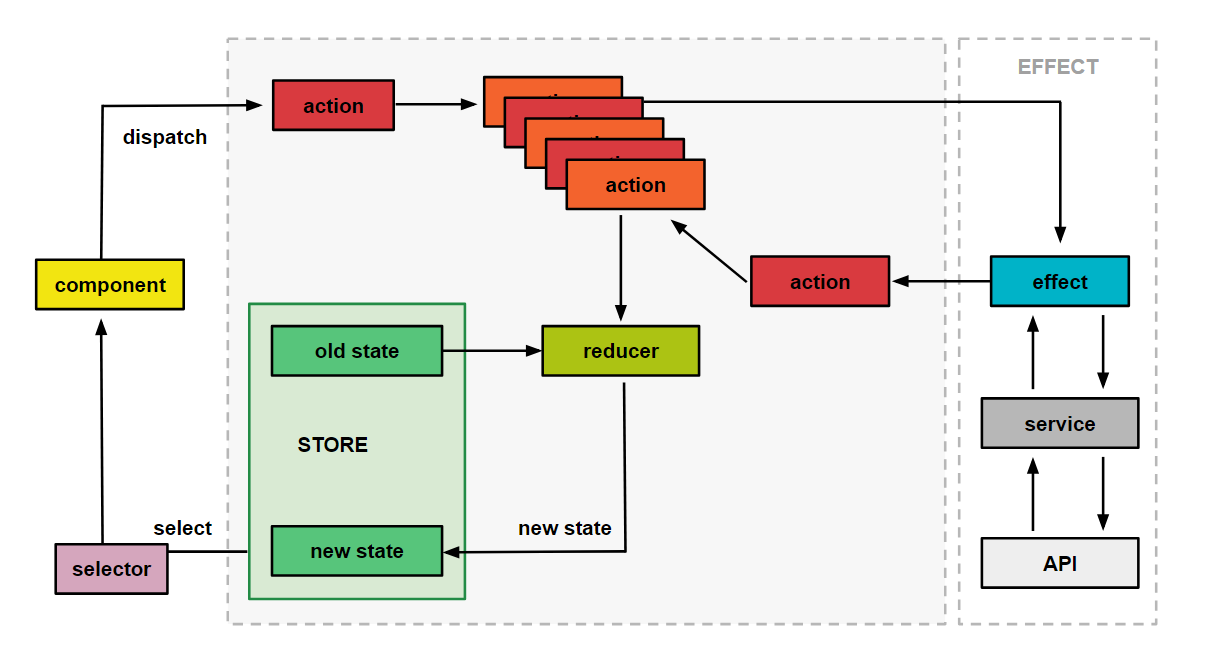

The most common approach to a more sophisticated state management architecture is known as the Flux pattern. A well-known implementation of this pattern is Redux, originally for the React library (Redux is not a purist implementation of Flux, but delivers the spirit of the pattern). ngrx/store is the Angular implementation of the pattern.

In Flux and ngrx/store the essential idea is to extract application state to a central (single source of state “truth”), then interact with it in a constrained way via commands (in ngrx/store, called “Actions”). Components that depend on the state respond to the state changes, but are insulated from understanding how the Actions operate on the state.

Reasons to Use a Store

More important than the question of how to use ngrx/store is when to use it.

Iron Clad Reason to Use ngrx/store

- You have race conditions as a result of multiple actors (ie, user, websockets and/or workers) interacting with the application state

Possible Reasons to Use ngrx/store

-

State management is complex

-

Component interactions are excessive

-

Multiple state manipulators are at work (ie, server-push)

-

Understanding state and its behavior is becoming difficult

-

Snapshotting of the state is important

-

“Undo” support is required

Bad Reasons to use ngrx/store

- Everyone seems to be talking about it and using it

The simplest solution that works is the one you want. Simplify!

Only add complexity when its *demanded *by the situation. ngrx/store adds complexity and overhead; therefore it must be justify itself by a clearly defined need. You should be able to answer the question in one sentence: “We are using ngrx/store in this application because blank”.

With all the preceding in mind, let’s take a closer look at how ngrx/store works and how it answers the needs defined in the list of good reasons to use it. You should be able to answer the question in one sentence: “We are using ngrx/store in this application because _____”.

How ngrx/store Fits Into Angular

Before we look at the Flux pattern and how store/ngrx brings it to life, it’s important to note that it is not always a necessary component in building an Angular application. Using ngrx/store brings more complexity, and that complexity should be merited by the requirements of the app being constructed.

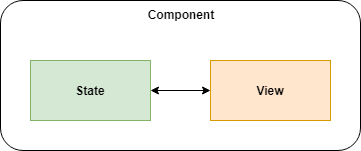

In a simple component, the store and view relate to eachother as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Simple Component with State

Figure 1: Simple Component with State

When this suffices, well enough. However, as you know, an angular UI is composed of a hierarchical tree of components. These components can interact via @Input and eventing.

In simple cases, these are enough to manage shared state.

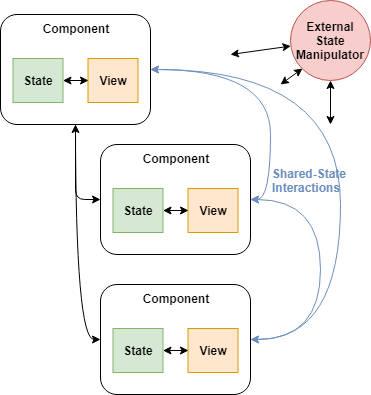

As applications grow, however, the inter-component interactions can become seriously cumbersome. It can become very difficult to understand and think about how events are impacting the state and how the components react to these state changes. Add to this the possibility of external actors on the state (like long-polling or server-push) and you have a strong case for using a central store like ngrx/store. This is seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Component Tree with State Interactions

Figure 2: Component Tree with State Interactions

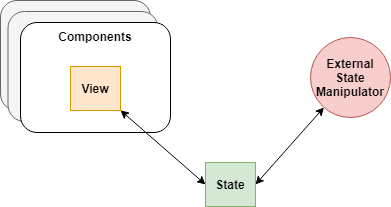

The solution to this problem is to externalize the state to central place, like you see in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Centralized State

Figure 3: Centralized State

Just like we create a state in a component and then allow the various view elements to reflect that state, the idea here is to move the shared state out of the component itself, and into a central place where all those concerned can interact with it.

Digging Into Centralized State

This is an easy idea to understand, and you may be wondering what ngrx/store does, since the above central-state idea could be implemented by injecting a global service into the components. This is a great question to ask. In fact, you may well be able to handle your applications needs by using shared services. Moreover, if you can identify subsets of components that use the same state, you can isolate your shared service state holders to smaller segments of the application.

Nevertheless, the idea of keeping all application state in a central place has a compelling simplicity to it. This is a central tenant of flux-thinking: one source of application truth. Therefore, let’s assume that you have determined your application merits a central state management solution. What does ngrx/store bring to the table beyond simply making a globally observable state?

Actions and Discrete State Changes

One prominent feature of ngrx/store is that it allows you to modify the state only via actions. An action is a single type of state change that components can invoke. An action is executed, and the component does not know about how the state is affected. This is a key element in isolating the components from the store.

You can think of an Action as a Command (in the sense of the classic Gang of Four Pattern).

import { LoadSongsAction } from './actions/songs';

import { Store } from '@ngrx/store';

import * as fromRoot from './reducers'; // The convention is to define fromRoot as our namespace for reducers import { Observable } from 'rxjs/Observable';

@Component({ selector: 'app-root',

templateUrl: './app.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./app.component.css'],

changeDetection: ChangeDetectionStrategy.OnPush

})

export class SongComponent implements OnInit {

public song$: Observable<song>;

constructor(public store: Store<fromRoot.State>) {

this.song$ = store.select(fromRoot.getSong);

}

ngOnInit() {

this.store.dispatch(new LoadSongsAction());

}

}An action is a simple command. Here’s a look at the simple LoadSongAction.

import { Number } from './../models/song';

import { Action } from '@ngrx/store';

export const LOADSONGS = '[Song] LoadAll';

export const SONGDELETED = '[Song] Delete';

export class LoadSongAction implements Action {

type = LOAD_SONGS;

}

export class DeleteSongAction implements Action {

type = SONG_DELETED;

}The action internally defines a constant, which convention uses a bracketed type definition followed by the activity given: ‘[Song] LoadAll’. This action can then be used as a discrete action that can be sent to the store.

Reducers

There are two places where actions come into the store: reducers and effects.

Reducers are pure functions, meaning they don’t produce side-effects (that is, they perform all their work internally to the function itself — another flux tenant). They are responsible for taking an action that is dispatched from the app, and applying it to the state. For example, in Listing 3, we define a reducer which applies the delete action.

export function songReducer(state = initialState, action: Action) {

switch(action.type) {

case 'DELETE_SONG': const songId = action.payload;

return state.filter(id => id !== songId);

default: return state;

}

}The numberReducer has a typical reducer signature: it gets the initialState and the action in its arguments. In this case, it takes a payload from the action, which will contain the id of the item to be deleted. The reducer then uses the id to filter the removed element from the state.

Effects

Effects, as the name implies, allow for side-effects. A common use for effects is to watch for actions which require loading data. Something like Listing 4 is typical.

@Injectable() export class SongEffects {

@Effect() update$: Observable<Action> = this.action$

.ofType(songs.LOAD_SONGS)

.switchMap(() => this.songService

.getRates()

.map(data => new SongsAreLoadedAction(data))

);

constructor( private currencyService: SongService, private action$: Actions ) {}

}This effect watches for the LOAD_SONGS Action, and uses a song service (injected into this class) to do that work.

Alternatives to Using Effect’s for Service Interactions

Although this can be a useful pattern, using effects to interact with backend services can become unwieldy as applications become more complex. This is because it can become difficult to manage the subscription and unsubscription from multiple components in the effect — if the user navigates away from the view, a new event type (e.g., CANCEL_LOAD_SONGS) can become necessary.

Moreover, if interleaving of requests is important to dependant components, it can become difficult to track when the data is loaded.

In short, effects can become a source of sprawling logic dependency.

Central Service Instead of Effect

Another approach that may scale better is to create a service that provides an observable to respond to requests for data from components, and allow that service to cache the data in the store. The decision of which approach to use it dependent on your application’s needs, and using an Effect to load data can work well for simple needs, and is an easy to understand approach.

Conclusion: Watch Your Agility!

The question of when to use a store like ngrx/store must be driven by the on-the-ground facts of the application. A strong indication of needing a centralized state is extensive shared-state and/or component state interactions.

This central state can be handled as an observable service at a variety of levels in the component tree, although a central state-of-record (ie, ‘one source of truth’) can simplify thinking about the application.

If a centralized state solution using subscriptions becomes untenable due to complexity, or because multiple concurrent actors are affecting the state (typically, this means server push like websockets are in play), then a formalized store like ngrx/store is the solution. This allows for rigorously defining what actions are applicable to the state, isolating them into Command objects (Actions), and concentrating the actual manipulation of the state into centralized and simple functions (Reducers).

My biggest beef with the store idea is that it is really anti-agile. You are adding all kinds of effort to doing anything in the app if you require everything to use the store. Especially, you are making it more difficult to change things going forward.

It could kill a project that might be agile enough to survive using just normal state-driven behavior.

Comments